- Home

- M. Ben Yanay

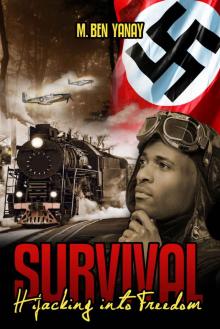

Survival

Survival Read online

Survival

Hijacking into Freedom

M. Ben Yanay

© All rights reserved by the author Motti Ben Yanay

This book must not be photocopied, recorded, scanned, stored in any databases, or published either fully or partially in any manner or form on any electrical, optical, or mechanical device, or distributed fully or partially in any form or means, including the Internet, e-book, or by any other means, without the written permission of the owners of its rights.

Editor: Nitsa Tzameret

Translated from Hebrew by Guri Arad

Proofreading by Adirondack Editing

Contact: [email protected]

In memory of my parents and of my brothers Arno’ka and Sandor who did not live to reach the prime of life.

Prologue

The truck Janos St. Claire had been driving was the third in a convoy of twenty supply trucks operated by Hungarian Army forces. The trucks had been carrying food supplies and ammunition to the German Army’s Wehrmacht forces that had been besieging Leningrad and its outskirts, amid the fighting against the Red Army.

The harsh Russian winter had ravaged the besieged and the foreign invaders alike. Harsh starvation plagued the city, which—apart from a narrow passage along the “Road of Life” established across Lake Ladoga—was completely cut off from any supply lines.

The siege lasted nearly nine hundred days and was lifted only following bloody battles. The “Leningrad-Novgorod Offensive,” which began in a joint attack by the Leningrad front and Volkhov front forces on January 12, 1943, led to the fall of the German outposts in the south of Ladoga Lake and the breaching of a land corridor into the blockaded city.

Between June and August 1943, the Soviet forces succeeded, thanks to assistance by Baltic Fleet aircraft and vessels, in lifting the siege from the nearby city of Vyborg. The blockade was finally lifted a year later, in January 1944, and the Germans fled. As Allied forces in Western Europe made their way to Germany itself after the invasion of Normandy, the Soviet Union’s 18th Army kept pursuing the Germans in the east, pushing them back to their own border. The Red Army entered Germany in a dash to Berlin amid a race aimed at beating the West to the German capital and capturing it first.

In the ensuing chaos of the Wehrmacht’s retreat, many German units were left stranded in the now liberated Russian territories. Those among the German forces who did not surrender were mercilessly executed. Others, chiefly SS units, kept fighting from the pockets of land in their control, with the intention of rejoining the retreating German forces and returning to Germany.

Table of Contents

1. To Freedom

2. Terry

3. The Deportation

4. Between Camps

5. In the Thicket

6. A Crazy Idea

7. Journey into the Unknown

8. Ina On the Lookout

9. Changing of the Guard

10. “Lexy” the Locomotive

11. Janos’s Recruitment to the Fascist Army

12. “Lexy” on the Bridge

13. Magda von Keitel

14. “Blood for Goods”

15. The Test

16. Janos—“Lexy” Under an Air Raid

17. Janos—Tales from the Past

18. Adventures in the Foreign Legion

19. Final Days at Camp

20. Terry—Getting Acquainted With Janos

21. The Russians Are Coming

22. Bob—From “Sentinels” to Sky Guards

23. Janos and Terry — the Encounter

Epilogue

1. To Freedom

The first days of April 1945 indicated spring had come. For hours on end, the sun shone through the clouds, spreading light and a little warmth across western Russian soil. In the forest, the trees gave in to the promise of spring. Some branches shed their heavy coats of snow, and others proudly displayed their bare foliage. Nevertheless, winter lingered and resumed its blows with full vengeance. It seemed as though Winter himself was not about to acquiesce to Lady Spring. The days had been very cold, with heavy clouds hiding the sun and relentless snow. The wheels of Janos’s TATRA truck struggled with the frozen route, which the two trucks leading the convoy had been beating down. Cypress and spruce trees stood along either side of the road, decked with thick and heavy white overcoats.

The twelve SS men in the truck felt secure from any aerial bombing but were fearful of what the forest might bring. In the woods, bands of partisan combatants, and mostly Red Army units, were lying in wait, busy purging the territories of any German units that had remained trapped behind. The bulk of the German forces had already retreated, so the forces that had remained knew all too well they were surrounded, and that it would take a miracle to avoid those who sought to annihilate them.

In the cabin, seated to Janos’s right, was an SS Lieutenant, all tense and alert. His eyes kept screening the edges of the road, where the trees began. Every so often, the officer looked up to the cloudy skies and hoped they would not disperse. Sudden gusts swirled the snowflakes. All of a sudden, the snow ceased and visibility improved greatly. The officer looked up anxiously. The canopy of clouds broke. The cold, golden sun broke through the clouds, belying warmth, as the clouds blew eastward.

It was completely clear suddenly. The German grew worried still. Two MIG-3 planes dived over the truck noisily, firing at the convoy. A few bullets hit the truck’s left side.

“Stop!” the officer ordered Janos.

The aircraft shot up, ahead of another attack.

The SS men leaped out of the truck in the footsteps of their commander, running to the woods for shelter. Janos lingered for a bit, unfazed, hoping to escape the attack.

The two MIGs dived again, leaving behind two heavy explosions even before they took off again. One of the bombs missed the back of the truck, yet the blast caused the truck to rise in the air and turn over. The second bomb went off at the edge of the forest, its shrapnel hitting the other trucks and the fleeing soldiers. Desperate cries and shouts were coming from all over.

Janos suffered a slight blow. He looked for any wound and found none, so he crawled out of the driver’s cabin into the forest. He passed the first rows of trees looking closely left and right. He heard the sounds of the engines over the men’s voices. He suddenly saw a wounded German soldier lying next to two tree stumps, moaning heavily. Janos surveyed the seriously injured German calmly, took his rifle and continued his crawl on the snow into the forest.

The pair of planes did not return for another strike. Their noise died down until it was completely gone. As Janos kept crawling into the forest, all he heard were the branches’ silent whispers in the wind. He rose to his feet, placed the rifle over his shoulder and walked on.

For the first time in so many days, he suddenly felt buoyant. His feet stumbled deep in the heavy snow, yet he felt they were as light as a feather. He wanted to cry out into the skies, but he did whisper, “Istenem [My God!], I’m free.” His whisper burst out in growing joy.

His feet ran deep into the snow amid the trees. The thicket grew heavier still, hard to cross. He kept going for about an hour and then stopped, figuring out which direction to turn next in order to leave the forest. He had no idea as to his exact location. A shot cut his thoughts short. He stumbled into the snow and fell facedown. Two more shots were fired at him, one hitting a tree near him. His heart was beating fast. Fear was creeping up all about him. He moved, trying to hide behind a big stump. Then a loud order came in Russian: “Stop!”

Janos obliged and stood attentively.

The heavy footsteps in the snow drew closer. He raised his head, only to see a pair of black boots turning his own rifle away. In a glimmer of an encouraging thought, Janos’s mind thought I’m

saved. He slowly bent his back and knees to a sitting position, his hands over his head. A soldier in a Red Army uniform was standing over him. He had a savage beard and pointed a rifle at Janos. The soldier wore a heavy khaki coat down to his shin and had a bullet belt over his coat. He also had a pistol in his belt. The soldier wore a gray fur hat adorned with the Red Army star. Janos looked at him in silence.

The man ordered him in Russian, waving his rifle with a threatening gesture.

“I do not understand,” Janos replied in Hungarian.

“German?” the Russian asked.

“No. I am Hungarian,” Janos replied.

The threatening gesture with the rifle ceased. The Russian seemed to grow less vigilant. He motioned for Janos to stand, took his rifle and leaned on it. He cleared his throat and said to Janos, “Come with me.” He touched Janos’s back with the tip of the rifle. Janos walked on, and the soldier followed suit. After a short walk, they arrived at a clearing where another man and a woman stood waiting.

Maybe they are partisans, Janos asked himself hopefully but did not dare make a sound.

The man, who also had a savage beard, had a bullet belt complete with two impressive grenades. He wore a grayish fur coat and a matching hat. The woman was about a head shorter. A few flaxen strands of hair crept out from under the tight wool hat she wore over her head and neck. She had a nice look about her. Her long, thick woolen coat masked her figure.

The woman spoke in a stern, commanding voice. “Why did you not shoot him?!” she demanded.

Janos did not know what she was saying but gathered from her tone she was the one calling the shots.

The man who captured Janos and the woman exchanged a few short sentences, and then the woman turned to Janos and asked in German, “Who are you?”

“I am a Hungarian Jew. I fled the Germans,” replied Janos in German, yet another language he had added to his repertoire from the days he served in the Hungarian Army, in particular since he began delivering military supplies to the German forces besieging Leningrad. His German vocabulary was poor compared to his French, which he had acquired during his stay in Paris after he completed his service in the French Foreign Legion and remained in the French capital. In those days, the local film industry began cooperating with British cinema, so Janos was sent to London to assist in filming and production. After a few months there, he had already picked up English, albeit in a Hungarian accent. When he returned to Hungary, he purchased a camera and made a living as a traveling photographer in roving fairs across the country.

The woman went silent for a moment and looked him over.

“We’ll take him to the bunker,” she told her comrades and ordered Janos, “Onward, mister!” pointing at an imaginary route through the forest.

The four made their way through the wet thicket. It was a tough walk, made worse by the stiff heaps of snow. The branches kept the skies out of sight, and there was no sign of any wind or sunlight. The dark did not make it hard for them to make way. Janos did not even feel the cold, as his thoughts wandered. Am I truly saved? Are the Allied forces truly getting closer than ever? Is the Eastern Front really changing? And what of Terry and the kids these days?

He heard his captors speaking in Russian, unafraid to speak out loud. He realized they felt secure—that they knew their surroundings very well and that they were close to each other in some way. His captor walked in front, paving their way. The woman followed suit, Janos right behind her, and the other bearded man was fourth. From their conversation, Janos learned his captor’s name was Mishka, the woman was called Ina, and the other man was named Gregory.

The thicket grew less dense and a little brighter. Gregory slowed down, stopped, and beat his boots on the ground to shake the snow off. The woman looked back at Gregory and tilted her head toward Janos.

Mishka stopped a few steps further and said, “We’re here.”

The bunker was nothing more than a ditch covered in branches, some cut down with an ax and some that had broken off with heavy snowfall. Thin gray smoke rose from a metal pipe, about four inches wide. The smoke had formed a kind of cloud over the ditch. Janos looked in amazement and saw additional smoke pipes all around. He counted some five additional bunkers. The woman tightened her lips together and whistled. The branches moved a bit. Mishka and Gregory shifted a few branches, unearthing the opening.

Ina clasped her tailcoat and jumped in. Gregory motioned to Janos to follow suit. Mishka slid in, then Gregory. Janos stood inside as the two landed right after him.

Four men and two women sat huddled together inside, around a circular metal oven running on moist twigs. As the fire blew, the thick smell of the smoke hit Janos hard, and his eyes watered. Two of the men rose and one of them stood atop a wooden crate, busy straightening the branches overhead as the other man looked at what he was doing. Janos looked at this band of people and had a good feeling.

“Who is this?” asked one of the two women.

Ina quickly explained, “Mishka caught him in the woods, a Hungarian and a Jew. He says he fled the Germans.” She then added, “He needs to be interrogated.”

“Sit.” She pointed at the wooden crate.

2. Terry

A chill ran down Frau Stauber’s naked back. She stood in front of a mirror in the hall with her new frock on. The thin garment complemented her figure. Terry was at her feet, head bent and holding a pincushion and white chalk.

“How short would you like it?” Terry asked, looking up into the mirror.

“Start lifting slowly,” ordered Frau Stauber. “Now stop. This is the length I want. Make haste. I do not have all day to waste on you.”

Frau Stauber had come to Strasshof after her husband received his commission as Sturmbannführer [equivalent to the rank of Major in the Wehrmacht] and deputy commander of the concentration camp. They lived in a flat that had been commandeered for the use of German officers. They had a large living room and two bedrooms connected by a long hallway, at the end of which was a window that barely closed shut, with a lace curtain. The wind was blowing cold, and Terry was shaking. Her frozen fingers barely clasped the thin pins.

“What’s wrong with you?” Frau Stauber scolded her.

“Yes, madam, I’ll finish marking it in a bit,” Terry replied slowly and dutifully. Had she not feared for herself, she would have stabbed each leg deep into the pink flesh, causing the German woman to bleed in agony.

This was hardly the first time such thoughts occurred to her. Whenever she was ordered to provide sewing and alteration services to the German officers’ wives, she spent all the way to town hatching all sorts of vengeful thoughts. She once even thought of seeking revenge on the Hungarian women who laughed with their husbands each night, but with time, she focused her attention on their German counterparts. Terry knew all too well that such mad thoughts would not bring little Arno, her five-year-old son, back to life. She knew she had to obey the German ladies’ every word. Nevertheless, her thoughts lingered, and as long as she was harboring her thirst for bloody revenge, she felt as though she had done the deed, so a sense of relief appeased her tortured soul somewhat.

“They are all murdering bastards,” Terry muttered the forbidden words. How could you hurt him so, my little boy, the innocent child who has done you no wrong? These thoughts continued to pester her ever since her child was murdered in the ghetto.

*

Over the course of the first two days, the small boy was coughing and wheezing, but Terry still took him with her to the sewing sweatshop. Then, when he started breathing heavily and his temperature rose, she left him lying on the straw bed in the small room next to little Andre, whom she left with a tin cup and a cloth. “Wet his lips,” she said, as she left for work with Sandor, the eldest child. Soft snow was piling outside their building. They stepped deep into it and made their way to the large structure where the adults—men and women alike—had worked, sewing uniforms for the German Army. Like the other children, Sandor was part of the clean

ing detail, assigned to scrubbing the concrete floor and picking up remnants of strings and fabric. He also loaded finished uniforms onto a wheelbarrow, which he took to the shed, and helped out cutting and pinning fabrics over the white chalk markings.

When they returned home that evening, they found Arno moaning with fever, twisting and delirious. Terry did not sleep a wink all through the night. Stone cold, she sat by him and wiped his forehead with a damp piece of cloth, then wet her fingers with water to let him suck on them. Then, morning came. Terry decided to remain beside her sick child, hoping to ease his pain somewhat.

A few hours passed, and three gendarmes burst through the door violently, followed by a man in a neatly ironed brown uniform whom she recognized as belonging to the Hungarian fascist “Brown Shirts” militia. The fascist pulled out a handkerchief, faced her with disgust, wrapped his face in his handkerchief and shouted, “Quickly, woman, to work! You and both puppies!” pointing at Sandor and Arno.

“But my boy is sick,” she said. She remembered all too well saying, “He has pneumonia, he is sick.”

“I couldn’t care less,” the fascist reacted ferociously. “Do you hear me?! Get up at once! Take the little one instead.”

She got up from the mattress and stood helpless before him. “Please,” she begged, “the child is sick, I need to take care of him.” Her legs turned to stone. Her hands hung in midair like bound-up tree-limbs. She was out of breath.

“We will mind him, now off to work with you!”

He then looked at one of the gendarmes and ordered, “Now take care of the sick boy!”

The gendarme leaned over Arno, lifted him with one arm by one of his ankles and shook him upside down, the child’s head facing the floor. Arno gasped, trembling in the air. “Catch!” he called to his comrades and acted as though he was about to throw him in the air. Then, as though he suddenly changed his mind, he dashed the child’s head into the wall.

Survival

Survival